Picture Series

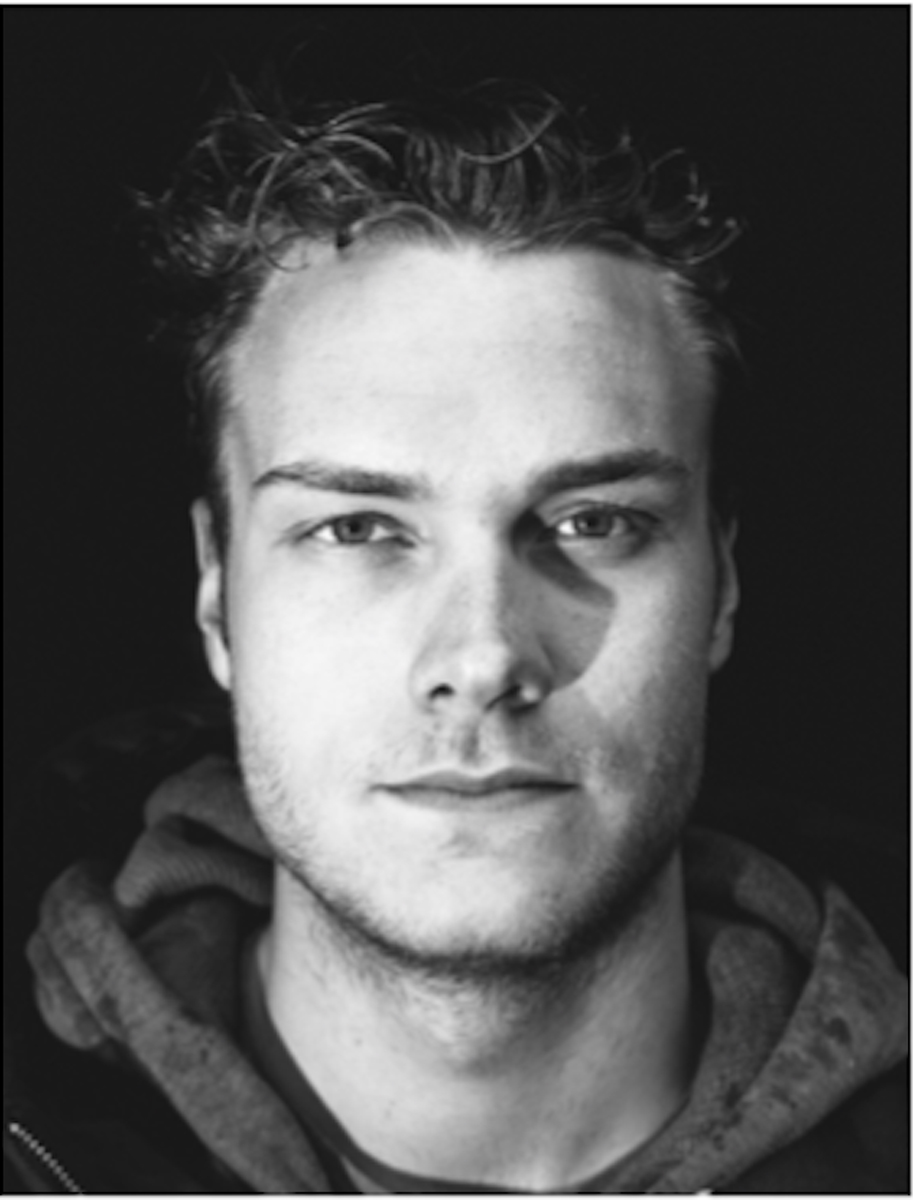

Maxime Matthys 2091 - The Ministry of Privacy

In the struggle against Muslim minority groups in Xinjiang province, the Chinese government uses modern surveillance technology such as facial recognition. In 2019, a data leak revealed that the Chinese company SenseNets is alleged to have used 6.7 million trackers to monitor 2.5 million people. “2091 – The Ministry of Privacy” examines the mechanisms of these facial recognition technologies. Kashgar is one of the last bastions of Uighur culture in Xinjiang. Maxime Matthys photographed people’s everyday lives here, then uploaded the pictures into facial recognition software that he developed with French IT engineer William Attache. The biometric data appear in the photos, document the dangers inherent in this invisible technology and blur the line between reality and virtuality.

- Digitisation

- Surveillance

*1995 in Brussels, Belgium

Maxime Matthys’ work connects photography, performance, video and installation. It deals with the question how technology influences our everyday lives and perception of reality. Along with these personal projects, Matthys documents current events. He studied Journalism and Photography in Toulouse and Paris. His work has been exhibited, distinguished and published internationally.