Picture Series

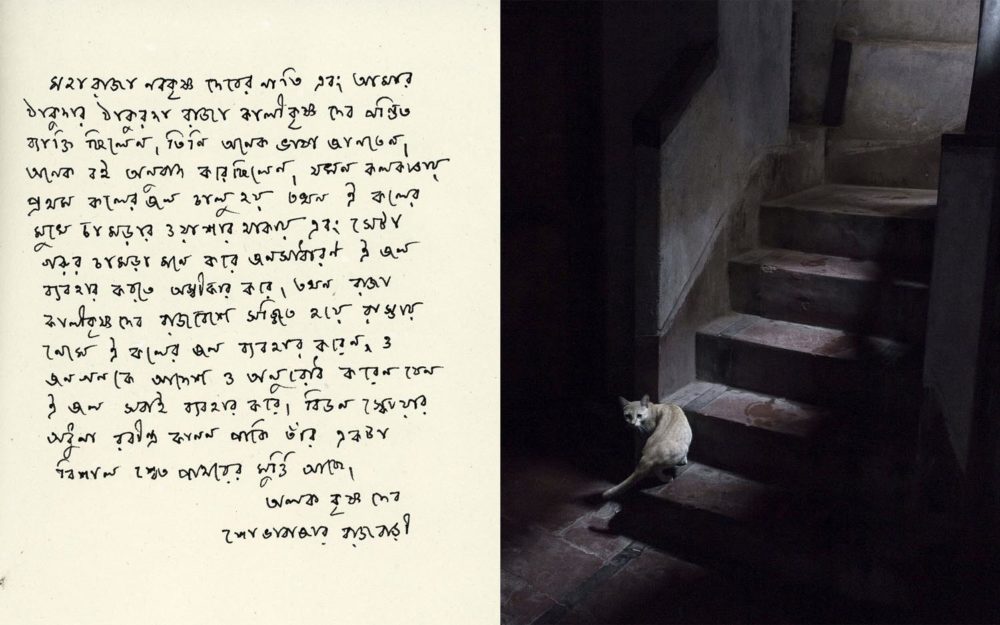

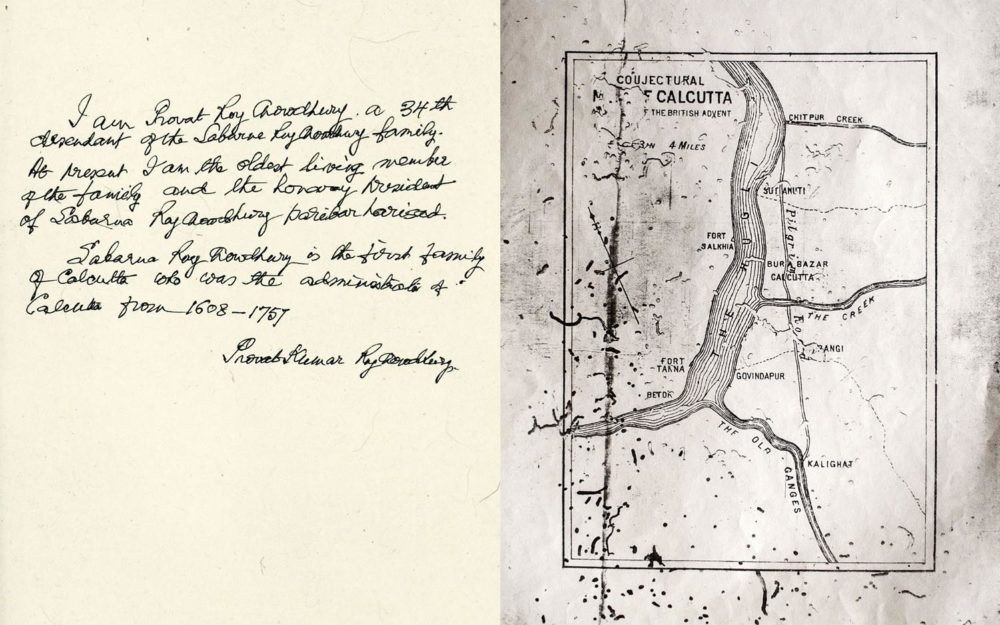

Santanu Dey The Lost Legacy

At the beginning of the 17th century, the British East India Company made Britain a colonial power in India, bringing great changes to the social order. In modern Bangladesh, the British established the zamindari system, which allowed a group of Indians who owned large tracts of land to enjoy privileges and wealth. With the end of colonial rule on 15 August 1947, the situation changed for the aristocratic zamindar families. Santanu Dey’s photo project looks at the descendants of the zamindars, whose families have played a significant role in the economic and cultural history of Kolkata and Bangladesh. Their contemporary descendants tell us about the era of decolonisation.

- Colonialism

- Discrimination

- Family

- India

- Memory

*7 July 1991 in India

Rather than continue his training as a financial bookkeeper, Santanu Dey took the opportunity to study photography at the Counterfoto Center for Visual Arts in Dhaka, Bangladesh. His social-documentary projects have earned many distinctions, most recently at the Jakarta International Photo Festival in 2019 and the Indian Photography Festival in Hyderabad. Dey won a prize in the 2019 Andrei Stenin International Press Photo Contest.