Picture Series

Alba Diaz The Pact of Silence

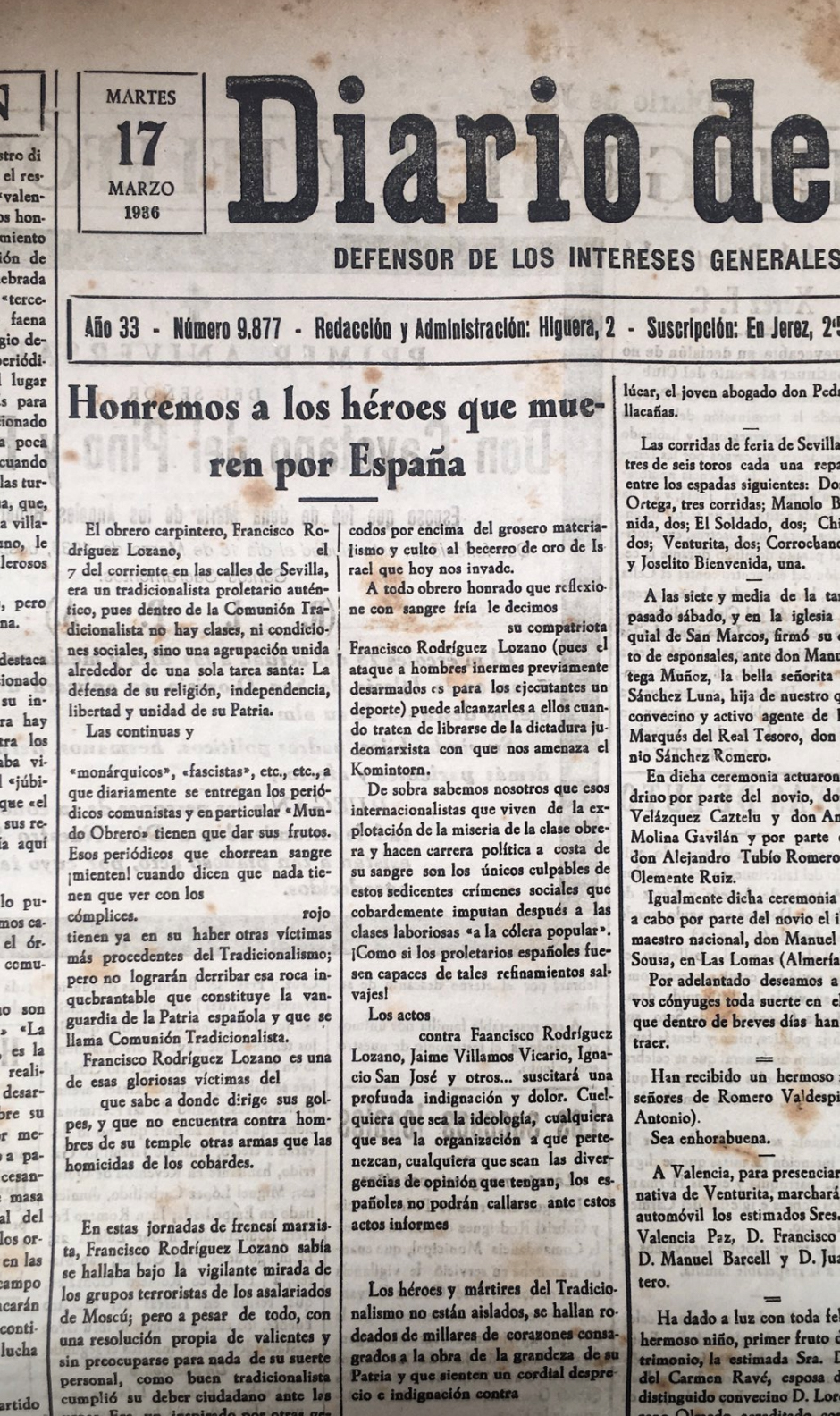

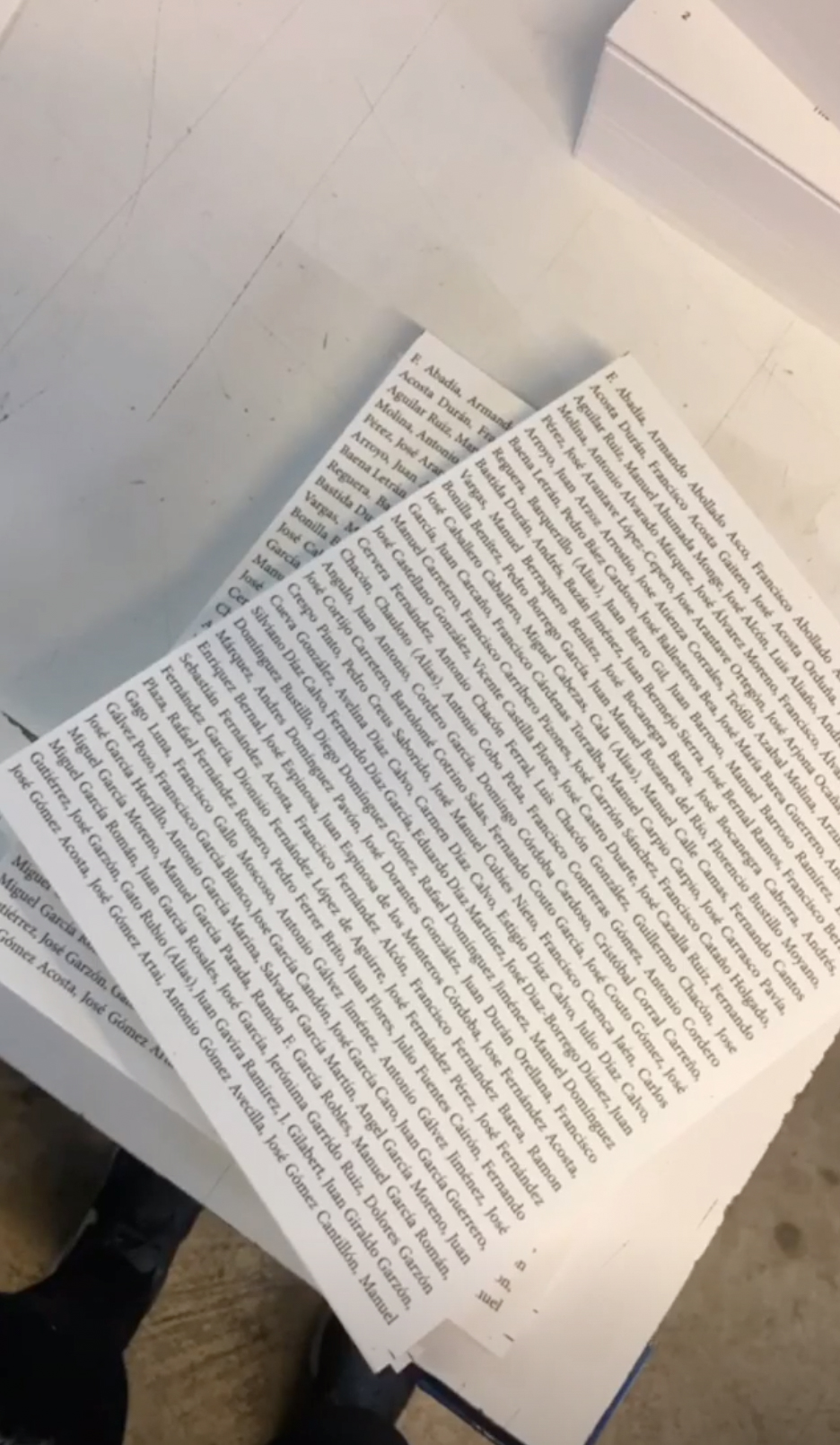

During the Spanish Civil War (1936–1939) and the subsequent dictatorship under Franco, hundreds of thousands of people were executed and buried in anonymous graves throughout Spain. José Montes de Oca, the photographer’s great-grandfather, was among those never found. Two years after the death of Francisco Franco in 1975, an amnesty law was passed with the aim of reconciling the divided country. This law guaranteed immunity from prosecution for all perpetrators; it is still in force today. The law became known as a “pact of silence” that would consign the crimes of the regime to oblivion. The picture series “The Pact of Silence” shows places of collective amnesia and aims to create awareness for the existence of the anonymous mass graves, some of which are located directly beneath homes, schools, parking lots and streets – places where José Montes de Oca could possibly lie buried.

- Family

- Fascism

- Spain

- Traces

- Violence

*1996 in Spain

Alba Diaz graduated with distinction with an MA in Photojournalism and Documentary Photography from the London College of Communication. Her projects deal with social, political and personal topics and follow a conceptual approach. Above all, Diaz is interested in clarifying the limits of photography and the challenges of photography as evidence. Her work has been exhibited in Barcelona, London and New York.