Picture Series

Sina Niemeyer Für Mich

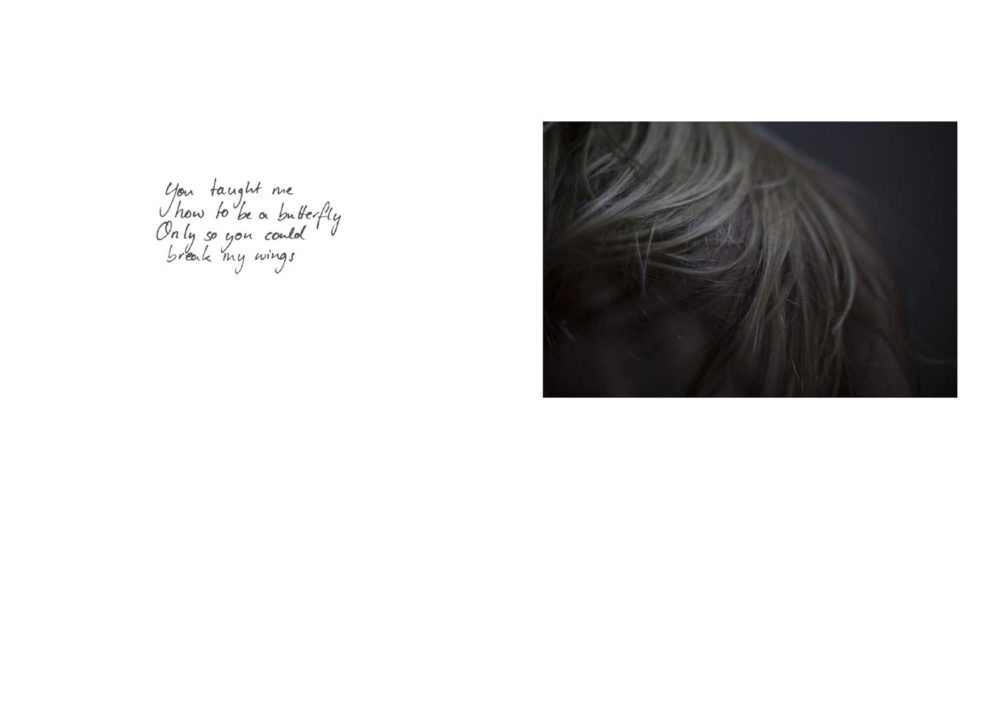

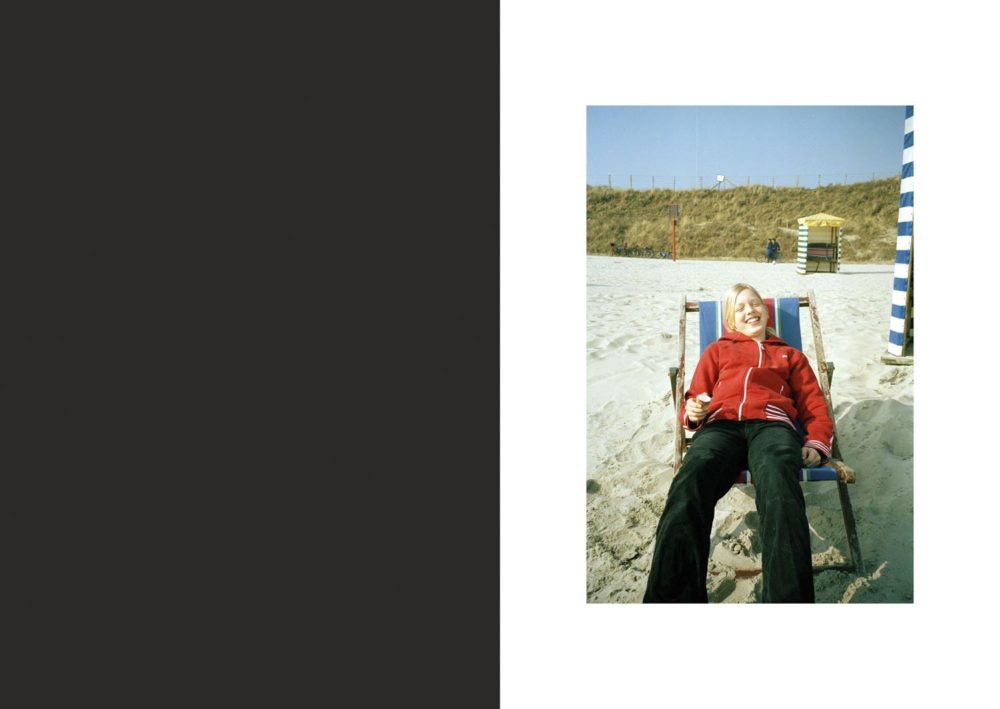

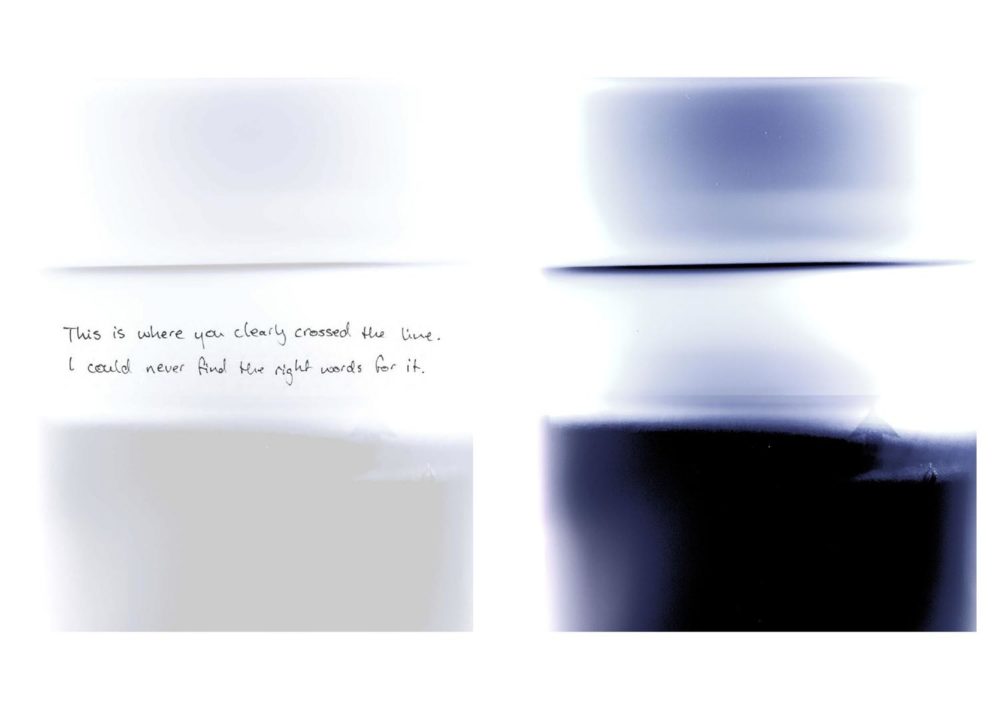

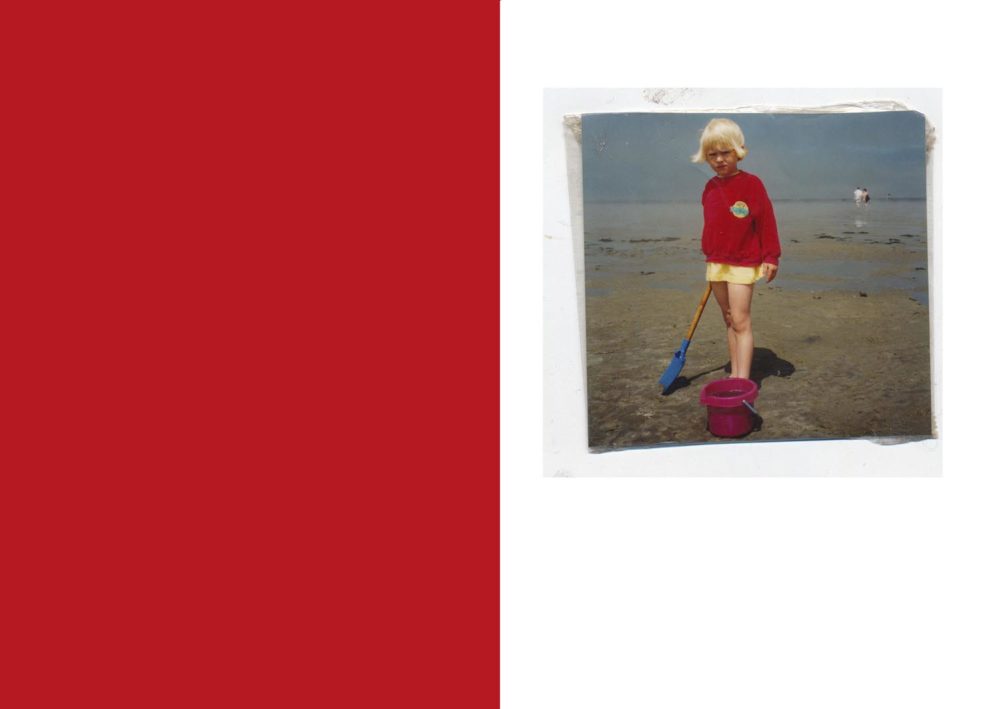

“You taught me what it’s like to be a butterfly, but only to immediately break my wings”, writes Sina Niemeyer in her diary. She combines various artistic techniques, photographs found objects, places and herself, destroys books and pastes them over. This is how she uses images and texts to relate how she was sexually abused as a child. It is a self-reflective revelation and an attempt to find her own identity. On different levels, she shows what sexual abuse can mean for a person’s life by visualising vague, subtle emotions that are often difficult to describe in words. According to statistics, every third to fifth woman faces sexual abuse in her lifetime. This project reminds those affected that they are not alone and hopes to encourage them to express their feelings in order to heal.

- Abuse

- Family

- Loneliness

- Memory

- Personal

- Story

*1991 in Germany

Sina Niemeyer studied Photojournalism and Documentary Photography at Hanover University of Applied Sciences and Arts as well as at the Danish School of Media in Journalism in Aarhus. Her work thematises intimacy, interpersonal relationships and feminism. With her final project “Für mich”, she won both the Young Talent Prize and the follow-up grant from “gute aussichten” magazine. The project has also been shown internationally. Niemeyer works for several German magazines and currently lives in Berlin.